Shawn and Marcus spent the last week in South Africa to discuss the continuous research work on systemic change, market development and innovation promotion. It was a week packed with a lot of thinking, discussion and occasional flicking through some of our favourite textbooks. Not much we enjoy more!

Continue reading

Is systemic change the same as increasing resilience?

I blogged before about the systemic change work I did last year. Recently, I have been reading up a bit on resilience and resilience thinking and was stricken by the similarity of the thinking between that field and what we have come up with as a way to see systemic change in market systems. Continue reading

The next step in systemic change

Over the course of 2016, Shawn and I worked on a piece of research on systemic change in market systems development, funded by the BEAM Exchange. In this work, we question the utility of the concept of systemic change in market systems development (though this is valid in the wider field of economic development) as it is currently used and suggest a rethink. To do so, we went back to search for a fundamental understanding of economic change. This is what we found.

Systemic insight: an alternative to Theory of Change

This blog has first been published on my personal blog site.

I have been blogging quite extensively about the Theory of Change (ToC) approach in recent months. My blog posts reflect a process that I have been going through as part of my different work engagements: adapt ToC approaches to be more sensitive to the complexities development programmes face in their day-to-day work.

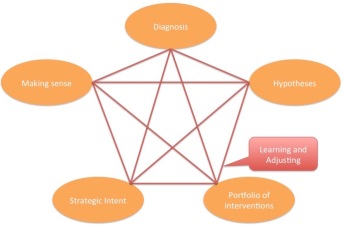

Different phases of Systemic Insight

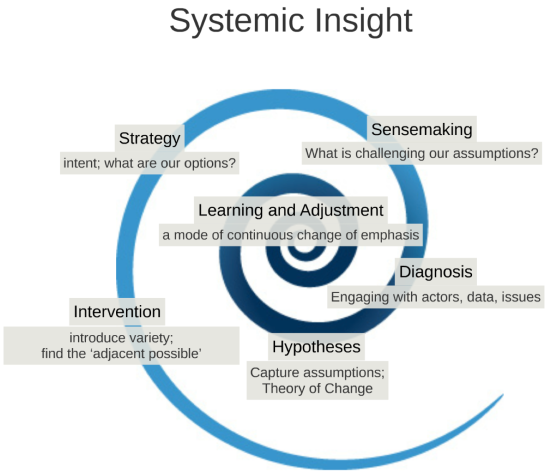

In parallel, with my colleagues at Mesopartner we keep doing research on understanding complex realities and our human reaction to them based on cognitive science, understanding the process of economic change, making decisions under conditions of uncertainty, and managing highly resilient organisations. In these contexts, ToC has limited applicability and a number of drawbacks. Therefore, we have been working on an alternative approach to the ToC approach which we built from the ground up based on our growing understanding of how complex systems work and how involved actors can lead a process of exploration and change. The approach is called Systemic Insight. Continue reading

A new framework for assessing systemic change

Over the last year or so I was hired by a large market systems development programme in Bangladesh to develop a new framework for assessing systemic change for them. We did an initial feasibility study and then a larger pilot study. The report of the pilot study has now been published. Rather than to bore you with the whole report, I would like to share the conceptual thinking behind the framework and the framework itself in this post. In a later post, I will share the methodology. This is not the end of all wisdom and the silver bullet framework everybody has been looking for. For me this is an important step to bring my work and thinking over the last couple of years together into something practically applicable. But this work is not done as I am embarking on a longer research project on systemic change. So there is more learning to come and with it more development of this tool. Please share your thoughts, which would help me to further improve the framework. Continue reading

Blog series on Theory of Change

If you are not following my personal blog, I would encourage you to check out my recent blog post series on the use of a Theory of Change approach in complex development programmes. There are four blog posts in the series:

- Complexity informed theory of change

- Adjusting a theory of change midway

- ToC – all harmony?

- Don’t over-design your ToC

Enjoy reading!

What different environments have in common from a leadership support perspective

In our work, we move between different environments. We work sometimes in development organizations, and on other days as advisers to business people. We move between assisting the Dean of a University to assisting a value chain practitioner in an NGO. Sometimes we help a policy maker, other days a team leader working in a rural location. We work with a diverse range of economic activity, from informal trading to retail, from home industries to advanced manufacturing, from agriculture to finance, local industries to international value chains. People ask us how we do this, what kind of expertise one must have to advise such different clients in such a wide range of industries.

The answer is actually quite simple. We are not engineers, nor are we knowledge workers for rent. We understand how to design processes of exploration and change; how to help people in systems recognize or become more sensitive to patterns and to then we assist them to carefully shape or influence those patterns. We have learned that a complex system does not become simpler by studying it. We also know that what people say they think and how they actually behave in the moment are not always consistent. Complex systems can only be understood by trying something to improve it and then carefully observing how the patterns change, typically through some low risk experiments or probes. These experiments must be done in a reversible way as far as possible, and should also try many different approaches to improving a particular situation. That means that without calling it that, we help organizations of all kinds to learn by doing. Most organizations simply pay lip service to this idea.

What decision makers in businesses, governments and development organizations all have in common is that they are trapped by long term visions of an ideal future state, trapped on narrow paths of the ideal way to reach their objectives. Planning instruments that work well within an engineering management environment have been applied to the management of organizations, of networks and of people. Many managers are frustrated because projects don’t go as planned, especially when it comes to collaborating with other competitors, counterparts, customers and supporters Their views of what is possible and acceptable behavior is often confined by ideology, organizational culture and inertia. Everything seems to be shaped or influenced by everything, and the consequences of making a wrong decision could undo the hard work of getting many other things in order through hard work. We have witnessed how in the last few years increasing numbers of leaders we work with have become despondent, risk averse and frustrated by instructions from above and demands from the outside.

A new blog post on Systemic Insight at IDS

Shawn and I wrote a blog post on the IDS website about our recent article for the IDS Bulletin. Here is how it starts:

The company we work for, Mesopartner, supports development organisations to address the challenge of innovation and change towards economic development, cluster and value chain promotion and the strengthening of local innovation systems.

In our work in economic development, we often find ourselves in situations where we don’t know which interventions will work and what exactly a good outcome will look like.

As a result, those working to plan and deliver development interventions may have divergent views on what must be done and why. These situations are complex (PDF) and uncertain (following Frank Knight’s definition of uncertainty).

Read more at the IDS blog …

Systemic Insight as a guided process of discovery

The first week of July is traditionally the week of the Mesopartner Summer Academy. This year, the 11th Summer Academy took place in Berlin – the 4th in the German capital. Systemic Insight was again a central pillar of this year’s Academy. We introduced it in a whole day session as a process of discovery in situations where solutions are not obvious.

A process guided by Systemic Insight enables organisations and networks of stakeholders to search for solutions to improve the performance of complex systems or emergent networks. This instrument draws on cognitive science and complexity thinking as well as experiences in the design of participatory social and economic change initiatives such as social labs or cluster platforms. At the same time, Systemic Insight was designed to allow stakeholders to work within complex issues without having to know the theories and understand abstract complexity thinking.

Systemic Insight is an iterative process where stakeholders explore the boundaries and constraints of a system in which the possibilities or solutions are unknown or uncertain. The format of collaboration, be it a multi-stakeholder platform or forum or purely bilateral interaction with the involved actors, is thereby not fixed but depends on the circumstance and can change over time. A high level of self-selection of participants into the process is encouraged. Self-selection means that local actors take ownership of the process by actively opting in, contributing to, investing in, and incorporating change in their own operations based on their interest to solve a problem or their identification with an issue.

In Systemic Insight meso level organisations are seen as central actors of change. Systemic Insight helps them to become more effective in managing change and resilient while assisting firms and networks to adapt to change in the environment. It shifts the focus of actors from responding to change towards actively testing ways to anticipate and actively create change.

The process enables stakeholders to challenge their own assumptions, discover and better understand the system and make sense of the constraints and possible opportunities. It guides them to intervene through portfolios of quick win activities or safe-to-fail experiments. Continuous learning and adjustment ensures an iterative and adaptive approach that is appropriate to tackle complex issues. In order to put learning and adjustment in the centre of the change initiative, monitoring and management functions need to be integrated to allow for decision making that is based on facts and current realities and needs.

As part of the Mesopartner research theme on complexity in development, we will continue to apply and further develop this approach. We seek to work with projects that are stuck and need a fresh approach to infuse the situation with discovery and innovative ideas.

Is target sector selection a good place to start

In much of private sector development, the selection of a particular economic sector or sub sector happens quite early in the development process. Typically a sub sector is selected either for its potential in terms of job creation, exports or some other criteria. These indicators are sometimes informed by some preliminary research, other times by careful statistical analysis.

Approaches such as market development (a.k.a Making markets work for the poor) often assume that if a market that is important to a particular sub sector can be improved, then the society (and of course the sub-sector) will benefit. This logic ignores that a market is deeply embedded in a social context, what Mark Granovetter called social embeddedness. Furthermore, market failures tend to be interconnected as markets are interdependent. Thus the chances that a market is failing for a particular good or services in isolation of many other markets is slim. Market development is an evolutionary process that requires the co evolution of product and service markets as well as market supporting organizations and systems (markets are about far more than supply and demand, unless you are a traditional economist). This evolution is enabled or hampered by the presence of social institutions like trust, habits, value as well as formal and informal organizations that provides market guidance, regulations that reduce transaction cost (for instance by providing quality assurance).

The chances that a particular sub sector and its supporting markets, say for instance dairy farming with its small farmer network that is connected to a retail market, will evolve as an exemplary island in a sea of chaos (as in disorder, randomness, inconsistent behavior, low trust and fragmented efforts to improve the system) is highly unlikely.

In these instances, a sectoral or sub-sectoral approach is futile. Of course, it could be argued that working with a particular sub sector reveals something about the society, an argument that we cannot disagree with. However, most development programmes are measured at the micro level (in other words at the level of the actors in a particular sub sector) rather than on the improvement of the overall system conditions which includes adequate or responsive domestic market supporting organizations and supporting social institutions.

If you really want to support faster change in a developing country, perhaps a more promising place to start is with the actors that are behaving differently from the rest. This is a very qualitative or subjective assessment, but with this group of outliers it may just be possible to prove that a different kind of behavior is profitable (or effective), and that the boundaries created by culture, habits and routines may need to be adjusted.